Letter 8: The Early Days of NFTs

On nostalgia, the past, and who came before us

When I started writing this letter Ethereum was still a Proof of Work system. By the time I publish it we’ll have already witnessed the successful (🤞) merge to Proof of Stake, the end result of a Beacon Chain created in 2020 to run parallel to POW and serve as a testing ground for something so much better.

If it’s successful (as I expect it to be) a whole host of changes are on the way, both for the users of Ethereum and, much more importantly, for the environment. With the future of Ethereum at our door, what better time to reminisce and take a stroll down memory lane?

Most people who have been in the space even for a little while know that if we’re being completely honest, NFTs were a blip on the radar before 2021. But even before the goblins, birds from the moon, multicolored squiggles, side-facing-anime-profiles, disinterested monkeys, or even our beloved punks, the space was alive and well with pockets of activity—albeit considerably different from how we might recognize it today.

In trying to determine which pockets I wanted to focus on, I realized that the subject of NFT history could be the length of Stephen King’s The Stand and still end up overlooking many important factors.

So, a definitive history of the space this is not. What this is is a tip of the hat to some of the projects I feel have meaningfully contributed to the space for one reason or another. And, since the history and significance of CryptoPunks is pretty well known by this point, I arbitrarily decided to exclude them as well as make the end of 2017 a cut-off date, affording me more time to spend on other relics. There are literally dozens of projects of significance I had to leave on the cutting room floor. Given enough time and a bit of luck, I’m sure we’ll get around to those as well some day.

Also, fair warning, but you’re bound to read the word “first” about a million times. Take it with a grain of salt. While the blockchain doesn’t lie, people have a way of stretching the truth or making unusually specific qualifications in order to substantiate their claims and maintain the title of “first”. You’ll be fine so long as you remember that nearly every aspect of the history of this space is hotly contested.

Colored Coins: The Proto-NFTs

When we think of NFTs, we rightly think of Ethereum. ERC standards are the backbone upon which smart contracts are built and issued. There is no blockchain which has done more for NFTs than Ethereum; its competition has, for the most part, had to settle for a drastically smaller share of the market.

But while NFTs undoubtedly would not exist as they are without the Ethereum blockchain, if you look closely, there exists the seeds of what would become NFTs on its blockchain predecessor, Bitcoin.

So what are colored coins and where do they come from? Well, the earliest chatter seems to come from a blog post by Yoni Assia (CEO of eToro, a multinational financial services company) on March 27th, 2012. Though these were the genesis musings of what might become colored coins, it was not particularly fleshed out. It would take well over half a year for that to come.

On December 4th, 2012, Meni Rosenfeld published a paper listing many potential applications and possible implementations of colored coins.

But it wasn’t until 2013 that we’d see the means of how that might work. It was then that Meni Rosenfeld, Yoni Assia, Rotem Lev, Lior Hakim, and future Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin would co-author the Colored Coins whitepaper, wherein they described a process in which Bitcoin could theoretically add and process metadata.

In doing so, this metadata of colored coins could help distinguish it from other assets, which carried with it a number of benefits and potential uses: not the least of which was enabling a method to allow digital assets to be ascribed other forms of value (real world or otherwise). Colored coins represented a new layer: an open source protocol where this metadata or “color” could be used to identify and repurpose what an asset represented.

There was a problem, however. The external value of these colored coins were not dependent on Bitcoin’s price, but solely the agreed upon value of the underlying asset.

Agreed upon being the key words.

Bitcoin was never designed to enforce agreements between parties in such a manner: if an issuer and their peers could not agree to redeem said coins for the stated/intended asset, then the process would be futile. As such, colored coins have always been somewhat like a chain; and like a chain, it’s only as strong and useful as the weakest link.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that Vitalik’s future creation, Ethereum, did away with this problem in the form of trustless agreements otherwise known as smart contracts. In smart contracts, the parties involved are irrelevant—it was only the code that mattered, and it would execute exactly as it was written.

Bitcoin was built as a currency first and foremost, and not meant to operate in the same way as Ethereum: as such, Colored Coins, as innovative an idea it was, could never be more than a band-aid for the many technological limitations of Bitcoin.

Even still, Colored Coins were an an amazing proof of concept of the technology which could one day change the space.

Although highly limited in their ability and functionality, some (including Colored Coins co-author Yoni), have gone so far as to call them the first NFTs, as they contained non-fungible elements in the form of metadata and resided on a blockchain (albeit with highly limited features).

Today, the colored coins vs NFT debate is one that many in the mainstream don’t appreciate, but the basics are simple enough to grasp. Non-fungible tokens are being used to represent digital artwork, i.e., a non-monetary asset. This is what colored coins were designed to represent. Thus, both colored coins and NFTs can represent real-world assets. The holder of an NFT is recognised as the owner of said asset, something that everyone can verify thanks to the blockchain.

- Excerpt from an article by eToro

While Yoni has a point, I also feel that it’s a bit of a reach. Given the incredible amount of limitations and being almost unrecognizable from what NFTs are today, I prefer to see it as a stepping stone; a “proto-NFT” if you will—a primitive precursor and forerunner of the space that was to come.

Quantum: The First NFT

There is a certain amusing quality to the fact that while the vast majority of NFTs today are static, the first NFT was in fact a .GIF. Minted by Kevin McCoy May 2nd, 2014 on Namecoin block #174923, the NFT space began. Don’t know what Namecoin is? Don’t worry, we’ll get to that in a bit.

Kevin McCoy is a media and digital artist based out of New York. His work Quantum was further refined by technologist Anil Dash.

Unlike Beeple’s work which sold for 69 million dollars in March of 2021 and arguably set the space alight, Quantum went for a meager $1.47 million in June 2021 when it was sold at Sotheby’s “Natively Digital” auction.

The story of Quantum has not been without drama, as it spawned a lawsuit over the rightful owner of the asset and whether rights to it had lapsed (Namecoin, which Quantum was minted on, has a peculiar requirement to periodically renew assets). Part of the dispute also revolves around the fungibility of the asset, as it was sold on Ethereum, a blockchain that it wasn’t originally minted on. One could argue that while the work was still his, the token was neither his, nor the original.

*Note: at the time of this writing, I am unaware of any resolution to this lawsuit, whether it has been settled, or even if it is still pending. If anyone has heard of a definitive resolution to the case, please let me know and I’ll amend the article!*

Namecoin: The Little Bitcoin Clone That Could

Namecoin (NMC) has the honor of being the first fork of Bitcoin, launching April 18th, 2011. Essentially a Bitcoin clone that operated in many of the same ways, the main differentiation between Bitcoin and Namecoin was what the technology was used for. While Bitcoin is first and foremost a cryptocurrency, Namecoin was a means for—what else—naming and identification. The changes which do exist between the two blockchains mostly comes down to different consensus and protocol rules.

The NameCoin blockchain software operated in such a manner that seems incredibly foreign and unwelcome in today’s climate: at a max of no greater than 35,999 blocks, the user would have to renew their name, otherwise it would expire and they’d lose control over their asset. A transaction fee was incurred each time a renewal was made as well. Due to the changing rate at which blocks were processed, this generally meant that people had to update every 200-250 days to ensure they retained control. Not exactly consumer friendly or convenient.

That is the crux of the aforementioned Kevin McCoy lawsuit, as it is claimed that McCoy had let the ownership of Quantum expire, which meant that the NFT went unclaimed, and his rights to it were forfeit, at which point a Canadian company called Free Holdings purchased the rights to it, undermining Kevin’s right to sell it in the first place.

Counterparty: The Bitcoin 2.0 Open-Source P2P Platform

One of the earliest Bitcoin 2.0 platforms, Counterparty, launched January 2014, was created by three founders as a P2P open-source platform that allowed people to make and trade assets or currencies. Although it was an early Bitcoin smart contract platform that could not send or control Bitcoin, it grew in prominence for, among other things, meme trading. Counterparty facilitated many of the earliest digital tradable assets, with the promise of avoiding counterfeits and forgeries—a problem present in all collectible communities in the real world.

The means of being able to prove ownership is a cornerstone that all blockchains today still hold essential.

Monegraph: The First NFT Platform

Founded November 20th, 2014, Monegraph is yet another gift from Anil Dash, the technologist and CEO of Glitch, and artist Kevin McCoy, who brought the world the first NFT, Quantum.

As the story goes, the two had known each other for less than two days, and they were matched together for Seven on Seven, Rhizome's annual 24 hour hackathon in New York City. As Anil describes it on his Medium article:

Kevin McCoy and I were batting cleanup together. Kevin and I had met just 48 hours earlier, with no introduction and little instruction except that we would have one day to create something we wanted to share with this audience. Within five minutes of our initial introduction, we knew exactly what we wanted to build. Each of us had been ruminating about the potential applications of Bitcoin’s block chain technology to the realm of digital art for months. Given the pedigree of the event, we knew we would have to at least present an idea worthy of Seven on Seven, even if its execution were necessarily compromised by the 24-hour deadline on which it was created.

I’ll skip past the typical hagiographic creation myth here to instead emphasize the fact that much of this idea was not novel. Indeed, many people have been pondering this exact combination of art and technology — enough that Kevin and I asked each other several times, “Why the hell hasn’t anyone done this before?”

And so it was that Monegraph, a product quickly slapped together on Namecoin, and a portmanteau of monetized and graphics, became the first digital platform to help artists sell and distribute their work.

Due to the cumbersome nature of blockchains and the complexities which might occur when dealing with a large amount of data, Anil and Kevin decided to use a URL in their Namecoin record. By using that URL and pointing it at an image elsewhere, they could keep the file size down, and show ownership between the author and the image.

This is more or less the same thing that a lot of NFT collections do today when they use The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). Unless the image is fully onchain, most creators will simply record the link in the blockchain which points to a hosted file off-chain, keeping costs and file sizes comparably lower.

Spells of Genesis

With their web version released in 2014, Spells of Genesis was a project that would establish a lot of firsts. They were among the first blockchain-based collectibles with their initial promo cards. They also helped fund their development by crowdfunding a native token which could be used in game. These days, we would call that an ICO (initial coin offering). By 2016 they had their full set of cards and the game in place. And, by April 20th, 2017, they were on the app stores of both Google and Apple and were one of the first multichain dapps.

When it launched it was the first blockchain-based mobile game. It’s hard to imagine now, but it did not launch on Ethereum in its earliest form—at that point is was only on Counterparty, the peer-to-peer, open source internet protocol which is built atop the Bitcoin blockchain and facilitated their in game currency, BitCrystals.

Cards came in two types: blockchain cards and in-game (off-chain) cards which were stored in the game’s database and could not be traded. It also contained a means of making cards “blockchainized” under certain conditions, which resulted in minting them onto the blockchain using Counterparty.

Spells of Genesis also dabbled with P2E (play to earn), allowing players to earn DAI tokens. An early example of a multichain game, it started on Counterparty (a financial platform built atop Bitcoin) before expanding to Ethereum and Klaytn.

Force of Will

フォースオブウィル (Force of Will) is notable as being one of the earliest examples of an already established game brand entering the blockchain space.

*Amendment note: Moonga, released by EverdreamSoft (the same developers of Spells of Genesis) in 2010 is arguably the first established game brand entering the blockchain space, as they already had over 250,000 downloads and a lot of traction by the time they implemented blockchain technology into their games. We’ll discuss this more in the next letter that we explore NFT history. Thanks to Wabi for the correction!*

The trading card game, reminiscent of Magic: The Gathering, debuted in Japan in December 2012 and went international in dozens of countries the following year. Immensely popular at its peak, in 2015 it was the fourth most popular collectible game, behind only the giants of Magic: The Gathering, Pokemon, and Yu-Gi-Oh!

So it should come as no surprise that it would appear on the blockchain not long after Spells of Genesis, in September of 2016, alongside their own token (WILLCOIN). Like SOG, Force of Will also got its start on the Counterparty platform.

There was even a battle simulator for people to use in conjunction with their cards.

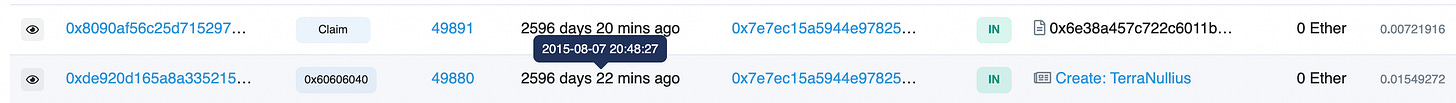

Terra Nullius: The First NFT on Ethereum

Just a week after the creation of Ethereum, the blockchain saw the release of its first NFT. Released August 7th, 2015, Terra Nullius (Latin for “Nobody’s Land”) was born, allowing its users to claim their own place on the blockchain, and in doing so share a message.

To my knowledge, it couldn’t do much else. As a very early project on Ethereum it lacked many of the bells and whistles of today, and couldn’t even be transferred.

Such limitations have of course spawned a few arguments. There are a lot of people who do not consider Terra Nullius an NFT because it cannot be transferred; to them, you can’t really own something if it cannot be transferred. Others say that it is indeed an NFT because you’re interacting with a smart contract on Ethereum.

It’s worth mentioning that the devs themselves never used the words NFT: instead, they called it “the first interactive Ethereum Contract”.

Whether NFT, “interactive smart contract”, or something else, it’s hard to deny the historical significance of something developed on the blockchain so soon after its release.

Etheria

Released on October 19th, 2015, Etheria is likely the first game on Ethereum and the first opportunity to own digital land on the blockchain. It was originally shown off at DEVCON 1, Ethereum’s first developer conference in London. The game itself is rather rudimentary by today’s standards—there are hexes, and you can own them, build on them, or farm them—but it was a giant leap for the space and was arguably unmatched for quite some time.

Etheria is a map of ownable, tradable, hexagonal metaverse land tiles on the Ethereum blockchain. Four fully decentralized, fully viable versions of the same 33x33 map were deployed in October 2015 and are now combined into a single map available for viewing here.

- From the Etheria website

The fun still remains to this day, as you can find Vanilla Ice, Ice Cube, and all sorts of random and wacky creations on the various tiles. I was especially amused by a certain SpaceLlama who reported on a particular Proof of Work hex.

As an interesting piece of trivia: according to their website, when Etheria initially deployed, ETH was sitting at the rather affordable price of $0.43 USD.

Rare Pepe: The Marriage of Memes and CryptoArt

2016 was a good year for building memes on the blockchain. That year, Rare Pepes launched as one of the earliest cryptoart projects as the community came together in a marriage of memes and crudely drawn art. Already an established internet meme for many years, the demand to make Pepe’s star shine even brighter could not be contained.

*Amendment note: the earliest cryptoart project was arguably The Scarab Experiment, which launched March 16th, 2015. We’ll explore that topic more the next time I write an early NFT article. Thanks to NFTRelics for the correction!*

This grew to such an extent that in September 2016, a marketplace/database of sorts was created by Joe Looney called RarePepeWallet, where trading card like images could be traded with their currency PepeCash (powered by Counterparty), or XCP (the native currency of Counterparty).

Far from a niche or whim, the works did not remain underground. For instance, the card below (My Little PEPE) sold for a million PepeCash, or the equivalent of $3500 USD in February 2017.

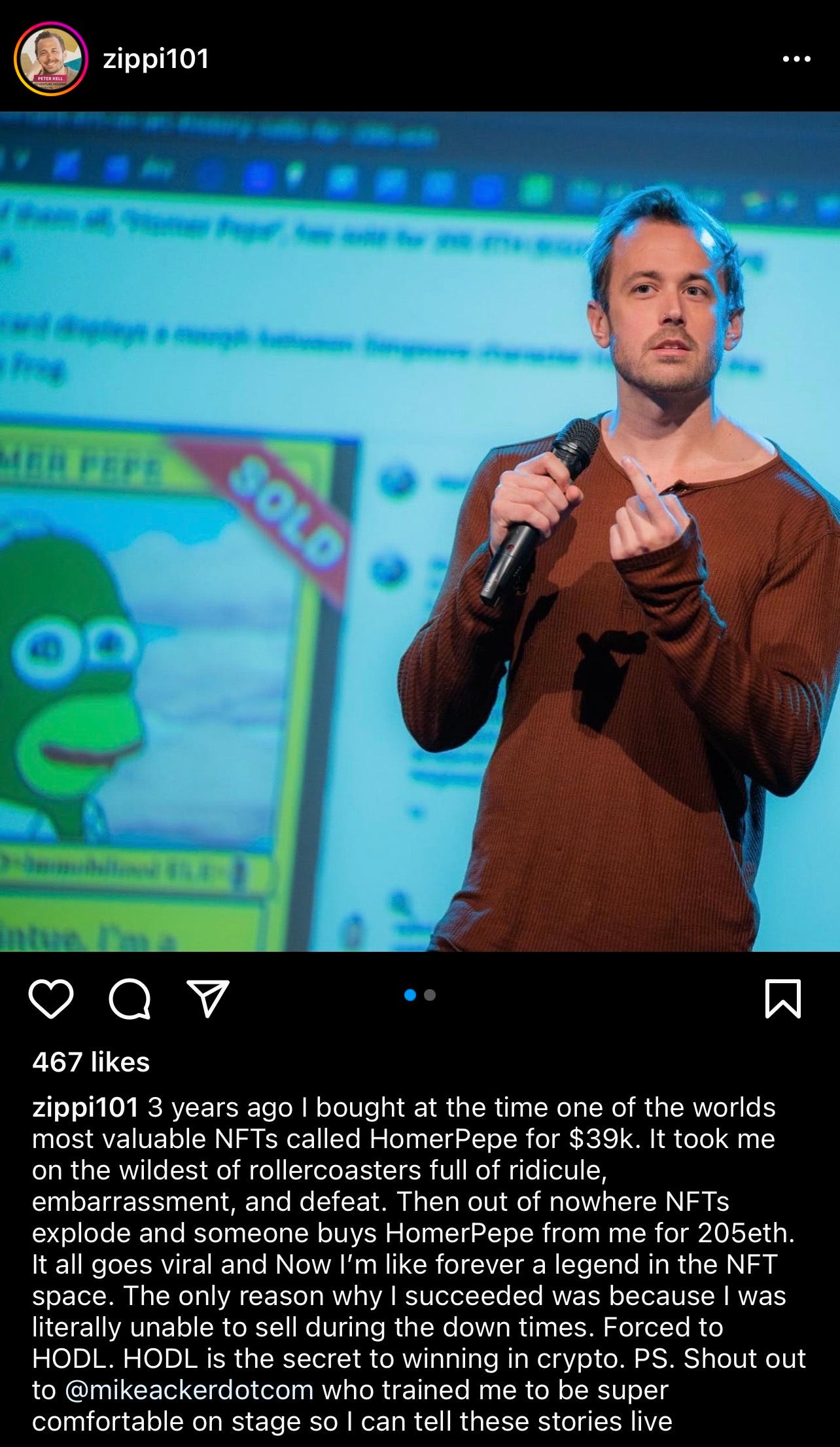

The following year, on January 13th, 2018, another Rare Pepe of notoriety—a Simpsons inspired Homer Pepe—was purchased by Peter Kell, a Florida based marketer in New York at auction at The New Art Academy.

Yes, there was an auction for Pepes. No I’m not making it up. It cost a cool 350,000 PepeCash, which was worth $38,500ish at the time of sale.

As the story goes, it was an impulse purchase, as Peter’s friends had recently gotten him interested in Pepe. Peter had just narrowly won a coin toss after a dispute arose over who had the winning bid. He was so new to the Pepe ecosystem that he didn’t even have a Pepe Wallet and asked if he could purchase it with Bitcoin instead.

Peter Kell resold the Homer Pepe a few years later in March of 2021 for 205 ETH (more than $300,000 at the time of sale).

EtherRock

Let it not be said that the early collections didn’t have a certain sense of humor. As one of the last notable releases of 2017 (December 26th), EtherRock is a collection of 100 rocks on the Ethereum blockchain. Art? It’s a rock. Utility? As much as a picture of a rock can offer. The color blue? Sometimes!

EtherRocks are without a doubt the Pet Rocks of the blockchain. What is a Pet Rock, you ask? Only the hottest toy of 1975.

Pet Rocks were the brain child of Gary Dahl, an advertising executive based in California. Each kit contained: a Pet Rock, a 32 page training manual, straw for bedding, and the box as a carrier (with air holes, so your pet wouldn’t suffocate). They sold for $4 a piece, and made Gary Dahl a multi-millionaire before people moved onto the next thing roughly six months later.

EtherRock is a very early example of a project which promised nothing. These so called “no utility” NFTs (in which almost nothing is offered to the user apart from the token itself) has run contrary to most of the NFT collections in the past couple of years: 2021 NFTs especially went out of their way to demonstrate all of their added utility and promising features.

These virtual rocks serve NO PURPOSE beyond being able to be brought and sold, and giving you a strong sense of pride in being an owner of 1 of the only 100 rocks in the game :)

- From the Ether Rock website

Famously, EtherRock only sold thirty rocks in the first three years of the project. That all changed in August 2021 when Gary Vee tweeted about older NFT projects and EtherRock responded.

Gary then quote retweeted EtherRock’s comment.

And before you knew it, EtherRock was minted out and the floor price skyrocketed.

As a side note, if you’re in the market as a seller, always double and triple check your price before listing your NFTs for sale. One of the most tragic burns I’ve witnessed in this industry occurred over listing an asset from EtherRock for wei instead of ETH.

Yep, a rock at a value of 444 ETH (around $1.2 million at the time of listing) was accidentally sold by @dino_dealer for 444 wei ($0.0012 at the time of listing) to a sniper bot.

This space can be ruthless.

2017: When Cats Discovered the Internet

The later half of 2017 was the point in which our feline companions began their move into web3. They could have been here sooner, but you know cats.

Anyways, three of the most notable cat launches of the year were, in order: MoonCatRescue, CryptoCats, and CryptoKitties, all of which would launch in late 2017.

MoonCatRescue

Deployed August 9th, 2017 before gradually fading into general obscurity, MoonCatRescue, a project developed by Ponderware, shares a story similar to EtherRock as another 2017 project to be rediscovered by the community several years later.

In MoonCatRescue’s case, it would be March 2021 before the cats would awaken from their nap. All it took was one mini tweet thread (attributed to @ETHoard) to bring it back into the public eye.

Because this was an early project, however, the process of “rescuing” the cats was not as easy as simply minting them. Instead, people interested in adopting a MoonCat had to first figure out how to navigate minting from the contract manually, as well as wrapping it themselves if they wished to list it on OpenSea.

Thankfully it wasn’t long until @0xAllen_ came up with clear instructions for the community.

Suddenly, the span of a matter of hours did for MoonCats what years couldn’t do before: the MoonCats were rescued. According to the devs, there were 4 billion possible combinations of cats which could have been minted; it was the community’s actions of rescuing the MoonCats which ultimately determined the final mix and rarity.

The devs and community manager of Ponderware touched on this issue of minting out in a later interview:

How soon did you start to see receptivity and engagement from your community?

A: The first week was pretty good, we saw almost 1600 mints. We put a lot of care into the whole experience of “rescuing” (minting) MoonCats and loved hearing about the fun people had “scanning” the moon (actually, mining) to find cats. When interest petered out over the subsequent years development paused, and we decided to simply support the interface in case, at some point in the future, people got interested again. And they did!

- Excerpt from the full interview between Ponderware and Mason Marcobello on behalf of Bankless

MoonCats remains as a testament to the power of NFTs and how even though a token may not sell immediately, the immutable nature of the blockchain ensures that it can be resurrected at any time by willing individuals.

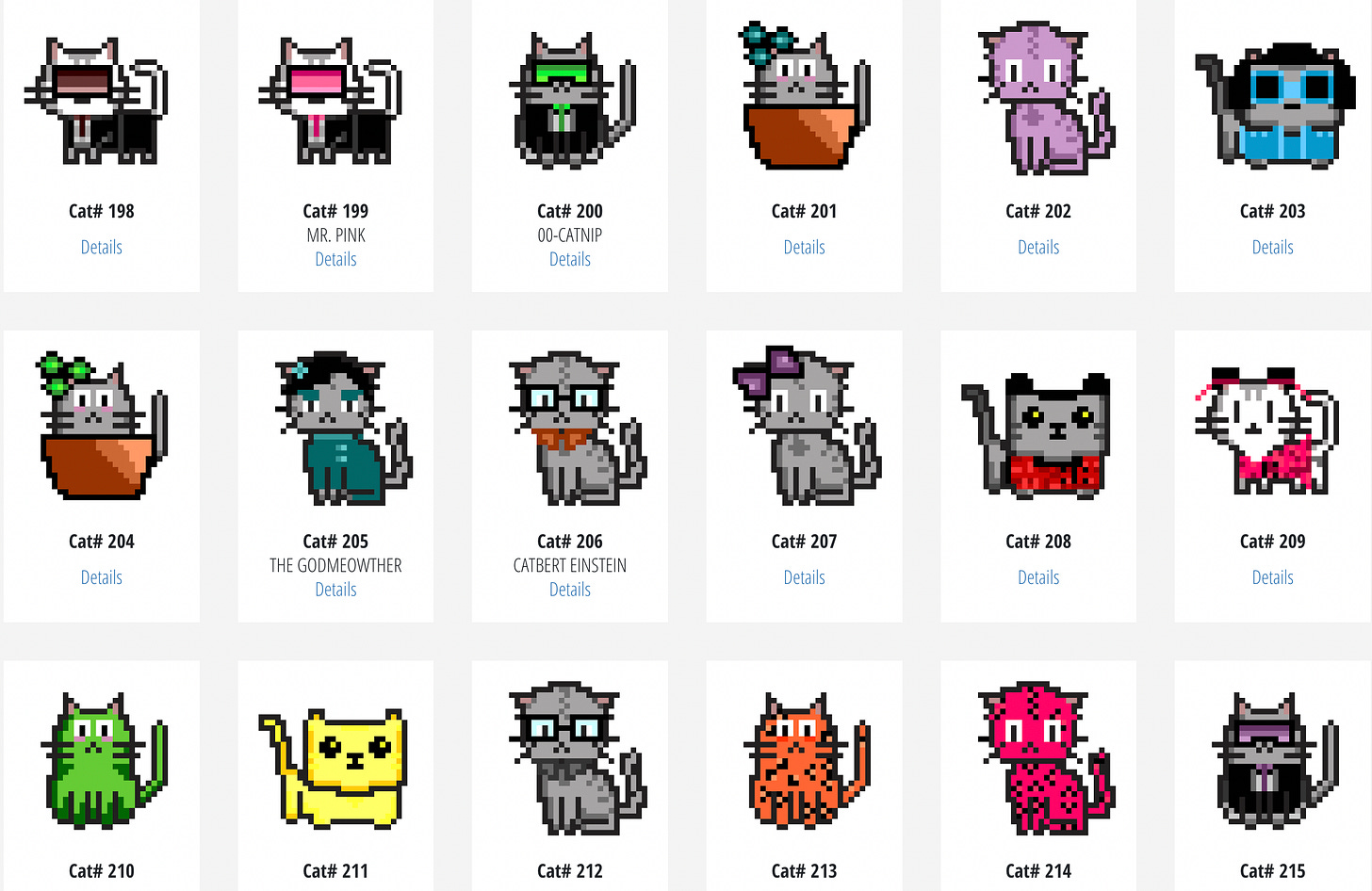

CryptoCats

First deployed on the Ethereum blockchain on November 12th, 2017, the CryptoCats collection was unique for its relatively limited collection size of only 625 felines, most of which were programmatically randomly generated with different accessories. Even though it was such a limited collection size, CryptoCats were actually made up of three separate contracts.

Supposedly, the team made it an internal goal to beat the CryptoKitties to deploying their smart contract (which they did). Additionally, some of the cats are of rather famous pedigree, as three of the so called “Punk Kittens” were made by Larva Labs, the creators of Crypto Punks.

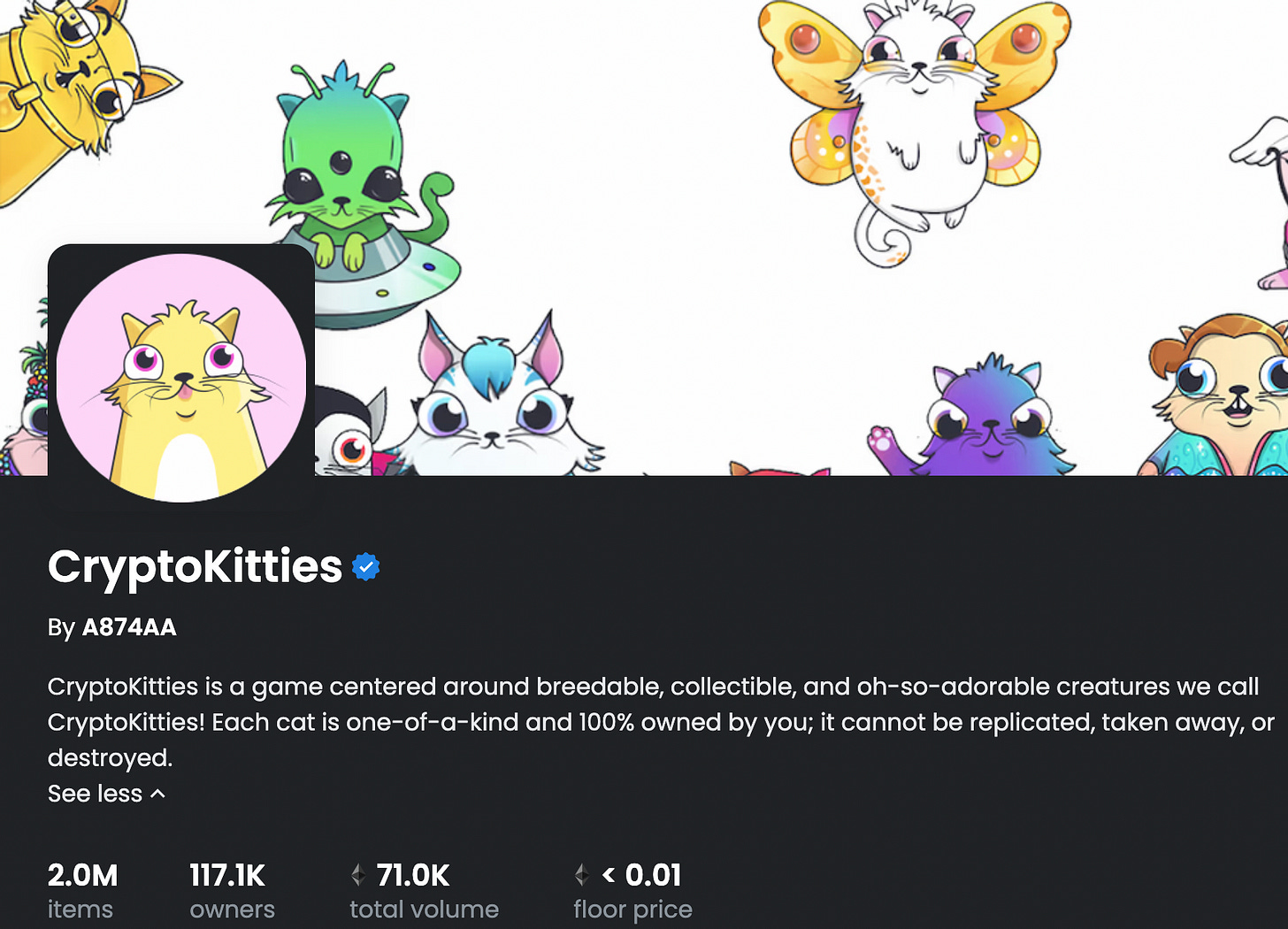

CryptoKitties

The cat NFT collection with perhaps the greatest traction (until Cool Cats would come along in 2021), CryptoKitties took the NFT world by storm straight out the gate.

The Hackathon at ETH Waterloo on October 19th, 2017 was the first time CryptoKitties made their public debut, winning first place and gaining the immediate attention of the entire community. This was followed by a release for beta testers on November 23rd, 2017, and then the public release five days later.

The sheer dominance of CryptoKitties in the space at that time can not be overstated. They were so successful that in December of 2017 they accounted for somewhere between 12-20% (I see conflicting amounts) of all transactions on Ethereum, badly congesting the network.

Like a great deal of amazing things in web3, it was made by Canadians: in this case, a company based out of Vancouver called Axiom Zen, who were already serial founders. And, as if creating one of the most significant and historical NFT collections of all time wasn’t enough, they also gave us Dapper Labs, the Flow blockchain, and you may have even seen them in the news recently for partnering with Ticketmaster over the issuance of NFTs for live events.

The rise of CryptoKitties was the perfect storm, as it went hand in hand with the bull market of 2017. The breeding mechanic introduced by the devs sent people on a frenzy of trading, buying, selling, and breeding their kitties.

Unfortunately, while breeding was by far one of the most compelling reasons for people to play the game, it also single handedly sunk the economy into irrelevance. There are currently over TWO MILLION CryptoKitties available on OpenSea, and 117,000+ owners. To put that into perspective, it was only recently that two million individual wallets bought an NFT on OpenSea. To say that these were deflationary is an understatement.

Still, their mark on NFT history cannot be denied.

Curio Cards

Created in 2017, Curio Cards are often claimed to be the first digital art collectibles on the Ethereum blockchain.

Curio Cards were a set of 30 cards (31 if you count an accidental misprint) made by 7 different artists, and was the result of a trio of creators: Travis Uhrig, Thomas Hunt, and Rhett Creighton.

The artists in question were (in alphabetic order): Cryptograffiti, Cryptopop, Daniel Friedman, Marisol Vengas, Phneep, Robek World, and Thoros of Myr.

In addition to being the first digital art collectibles, there were a whole lot of other firsts attributed to them as well, including: first NFT project to use IPFS, first Patreon model on the blockchain, first pen drawings on Ethereum, first rocket ship on the blockchain, first GIF on Ethereum, and more.

Curio Cards were one of the earliest attempts to do what all NFT artists have sought to do since: sell their work directly to consumers without a middleman (agents, galleries, etc). 100% of primary sales went to the artists; that being said, the cards were sold for practically nothing, for around a dollar.

Like so many historical projects from 2017, the project went dormant for years until it resurfaced and was rediscovered in 2021. And in the public’s haste to get ahold of them, a rather large blunder occurred.

In the process of trying to make the tokens compatible with OpenSea, a number of assets were improperly wrapped, causing tokens sent to the contract to be stuck (a term now known as “permawrapped”). This created a level of unintended scarcity and rarity, as Curio Card #26: Education became the rarest card, with only 105 remaining in tradable circulation.

A full set (including 17b, a digital misprint) were sold at auction in New York on October 1st, 2021 at Christie’s. They were sold to Taylor Gerring, an early contributor to Ethereum for $1.2 million. This was the first recorded Christie’s auction to eschew fiat in favor of ETH.

Ethereum Name Service (ENS)

Most of the people in the space today are familiar with the popularity of ENS (Ethereum Name Service). Much like how DNS (Domain Name System) helps users in only having to remember domain names (Google, Amazon, etc.) rather than the individual IP address of every website they wish to access, ENS are the web3 equivalent which takes the long and complex addresses of Ethereum and simplifies them to an easily rememberable NAME/WORD.ETH of your choosing.

There was the ENS boom of 2021, but what a lot of people don’t realize is that ENS is old. Older than CryptoPunks, even. It saw its start at the Ethereum Foundation (though it would later become a separate organization). ENS originally launched on March 10th, 2017, but as two bugs were soon discovered, they disabled the registrar and went to work on fixing it. The relaunch of ENS happened a couple months later, on May 4th, 2017.

Even Vitalik appears to be a fan of them.

As of the time of this article there are more than 2,183,091 Ethereum Name Service NFTs and 520,628 owners who have at least one ENS NTF in their wallet. One can only imagine how much they may blow up during the next bull run.

TL;DR Pre-2018 Timeline Overview

Apr 18th, 2011: Namecoin, a Bitcoin fork and clone focused on naming and identification/ownership goes live.

Jan 2014: Counterparty, The Bitcoin 2.0 Open-Source P2P Platform, is released.

May 3rd, 2014: Quantum, the first proper NFT, goes live on the Namecoin blockchain.

Nov 20th, 2014: Monegraph, the first NFT platform, is founded.

Dec 11th, 2014: The early development web version of Spells of Genesis is playable.

Mar 13th, 2015: Spells of Genesis releases their first of 42 promotional blockchain cards.

March 16th, 2015: The Scarab Experiment becomes the earliest art collective (development began in 2014) to launch on Counterparty.

Aug 7th, 2015: Terra Nullius becomes the first NFT on the Ethereum blockchain.

Oct 19th 2015: Etheria, the first game and land owning NFT on Ethereum, is deployed.

Sept 8th/9th, 2016 (conflicting statements): RarePepes becomes an early art collective on Counterparty. While not the earliest (that title likely goes to The Scarab Experiment), it was certainly one of if not the most popular of the early art collectives.

Nov, 2016: Force of Will becomes one of the earliest established game brands to hit the blockchain, on Counterparty (although the earliest established game brand was likely Moonga, on Counterparty the year before).

Mar 10th, 2017: ENS launches for the first time, finds two bugs, and takes a step back.

April 20th, 2017: Spells of Genesis is the first blockchain-based mobile game, available for download on both Apple and Android devices.

May 4th, 2017: ENS, having fixed said bugs, relaunches.

May 9th, 2017: Curio Cards becomes the first NFT artwork collection on Ethereum.

Aug 9th, 2017: MoonCatRescue goes live.

Oct 19th, 2017: CryptoKitties make their debut at ETH Waterloo Hackathon.

Nov 12th, 2017: The first (of three) CryptoCats releases is deployed.

Dec 26th, 2017: 100 EtherRocks grace the internet with all their rocky goodness.

🐼 Post-Merge Addendum 🐼

I was writing this article and watching the livestream when the Ethereum merge completed and felt that I should share a few words for such a momentous occasion.

Now that the ETH network has finally merged, the transition from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake is complete. Overnight, Ethereum has become an even more viable blockchain, not only for being perhaps the most flexible and adaptable, with the most robust smart contracts, but it may now also claim that it does so with massive reductions to its ecological footprint.

Estimates based on the current Beacon Chain suggest that The Merge to proof-of-stake could result in a 99.95% reduction in total energy use, with proof-of-stake being ~2000x more energy-efficient than proof-of-work. The energy expenditure of Ethereum will be roughly equal to the cost of running a modest laptop for each node on the network.

- From the Ethereum.org page Ethereum Energy Consumption

Vitalik Buterin, founder of Ethereum, also had a few words to share that night.

Vitalik also retweeted something that everyone in tech knows in their bones.

This is technological history in the making, and if you were there to witness it—guess what? You’re still early.

If you haven’t already minted your first NFT since the switch to Proof of Stake, what are you waiting for? I promise you, it’s safe. As for myself, my first POS mint was Merge Coin by NEOC, a commemorative coin and celebration of the ETH Merge, as drawn by digital artist Zsolt Kosa.

From all of us here at Curious Addys, we wish you a happy merge! See you September 30th for our next letter! 🐼 🐙

Written by: Brad Jaeger

Director of Content @ Curious Addys (say hi on Twitter!)

A few corrections.

1. OLGA is the first known NFT as in both "non-fungible" and "token".

2. If you include multi-issuance tokens (fungible "1/Ns") like SOG and Pepe, you can add JPGOLD and JPJA to the collection of firsts. All issued by JP Janssen in June 2014 together with OLGA on XCP.

3. Quantum, like all Namecoin domains, is not a proper token. Insofar as an image link is the NFT criterion, there were thousands on Namecoin prior to Quantum. It may be the first representing legal ownership, a model modern NFTs mostly have abandoned.

Great article . There is wrong info:

1-the web version of spells of genesis was playable starting in 2014, not 2016.

2- Force of Will wasn't the first already established game brand to hit the blockchain. The first one was Moonga.