Letter 9: How NFTs Can Save the World from Traditional Art

On digital innovation, a green Ethereum, and environmentally conscious artists

Anyone with eyes and a brain capable of processing information knows that we are in the midst of an increasingly escalating, manmade climate crisis. In the span of less than a few centuries since the Industrial Revolution began, humanity has abused its self-appointed position as stewards of the planet and placed it in peril, with no plant, animal, or landmass outside of our reach.

Environmental concerns are on the mind of many who are pushing the novel idea of preserving the earth for future generations. Meanwhile, the icebergs are melting, the water is rising, and carbon dioxide is at the highest levels in human history.

Enter NFTs, the digital boogeyman: once a not insignificant contributor to environmental pollution, these days they are anything but. Contrary to popular opinion, if you love art, love the environment, and want to see both flourish, NFTs are the best bet in town. This should not be a controversial statement anymore: in truth, much of the heavy lifting for a safer future began years ago with many of the digital transformations that have already lifted the arts into something more ecologically responsible.

NFTs are one of the newest technological innovations to come around, benefitting artists and the environment alike.

I’m here to argue that as artists we should take inventory and acknowledge some of the damage we’re causing in our pursuits, and realize that by embracing this new digital future (of which NFTs will play a part) we can all help in reducing the harm to the planet.

Bitcoin: Why the World Thinks NFTs are Evil

Bitcoin’s energy use is exorbitantly inefficient, wasteful, and an unnecessary drain on the earth. This is something that nearly everyone but the staunchest of Bitcoin maxis can agree upon.

In a well known study published in early 2021, Cambridge researchers crunched the numbers and came to the conclusion that Bitcoin uses more annual electricity than all of Argentina, at a whopping 121.36 Terawatt-hours (a Terawatt is one trillion watts). While that number certainly fell along with the crypto and NFT markets at the onset of the bear in 2022, the reverse is true as well: we can expect that similar or even greater numbers may occur in the next Bitcoin bull run, as more people join the network and drive up energy costs from miners.

As the first and most dominant blockchain, it understandably bears the lion’s share of the public’s ire. I’m not here to debate that, and agree that Bitcoin needs to be pressured to develop and implement more energy efficient means of operation. To be fair though, Bitcoin was the first of its kind, and the first of any technology is always going to be the least efficient: it’s through further development and iterations that technology becomes cheaper and more energy efficient.

A lot of the misdirected anger towards NFTs comes from how the Ethereum blockchain (the largest purveyor of NFTs) used to have something in common with Bitcoin — an incredibly wasteful Proof of Work system. And, as NFTs require computationally more effort to record on the blockchain than say, a simple crypto transaction, Ethereum was, for a time, contributing to this wastefulness. Once again, I’m not going to argue that (although it should be noted that even at its worst, Ethereum was never as wasteful as Bitcoin).

So why does Bitcoin require so much energy? It all comes down to how it adds blocks to the blockchain. Long story short: miners on their network put their GPUs to the test through a series of trial and error, attempting to solve difficult mathematical problems in order to earn Bitcoin. This ongoing and repeated process requires a great deal of electricity.

Ultimately, the combination of a public ignorant about the benefits of crypto and NFTs, coupled with the objectively poor and inefficient blockchain that is Bitcoin, has put every blockchain to come after in a negative light, regardless of whether or not it is justified.

Next, we’ll make our way to the NFT industry leader, and the good news of its transformation to a green blockchain.

99.95%

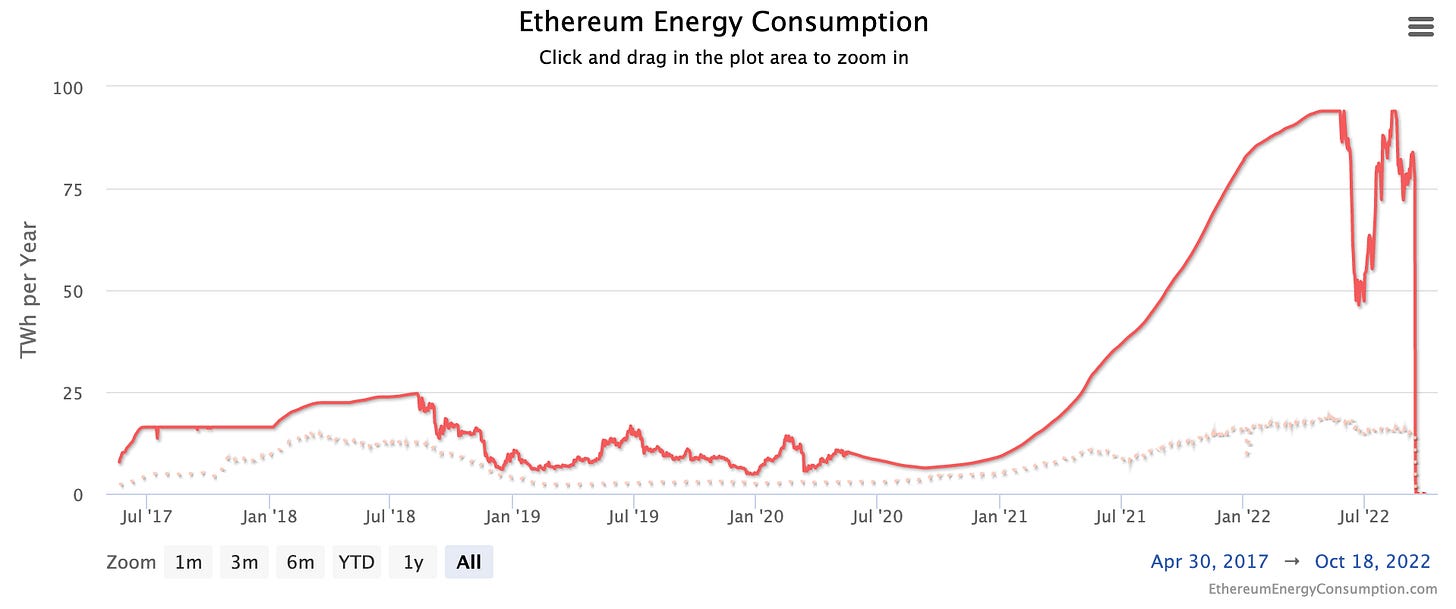

On September 15th, 2022, Ethereum, the blockchain market leader of NFTs by a country mile, transitioned from a Proof of Work system to a Proof of Stake system, after years of rigorous testing and running on a parallel Beacon Chain in preparation for “the merge”.

As expected, the public largely remains unaware of this development, but the results are still no less impressive. In an amazing feat of technical wizardry, Ethereum became ~99.95% more energy efficient overnight. Now it rests not only among several other (significantly smaller) green blockchains, but it is also objectively far less of a burden to the environment than nearly any traditional art.

Digiconomist had previously calculated that Ethereum miners consumed roughly 44.49 TWh per year. As of September 15th, 2022 however, Ethereum is ~2000x more energy efficient based on conservative estimates.

Ethereum.org had this tidbit to add:

If energy consumption per-transaction is more your speed, [Ethereum is] ~35Wh/tx (avg ~60K gas/tx) or about 20 minutes of TV. By contrast, Ethereum[‘s old] PoW [system] uses the equivalent energy of a house for 2.8 days per transaction and Bitcoin consumes 38 house-days worth.

Initially, the Beacon Chain shipped separately from Mainnet. Ethereum Mainnet - with all its accounts, balances, smart contracts, and blockchain state - continued to be secured by proof-of-work, even while the Beacon Chain ran in parallel using proof-of-stake. The Merge was when these two systems finally came together, and proof-of-work was permanently replaced by proof-of-stake.

Ethereum has now shifted to around 0.01 TWh/yr. That's 26x less than PayPal’s energy usage and 24,400x less than YouTube—in fact, it’s now known that people collectively consumed 45 times more energy watching Gangnam Style in 2019 than ETH now uses in a year.

This is great news for the planet and NFT enthusiasts, and bad news for your friends who no longer have one of their two main talking points. With the energy argument finally settled, they have no choice but to revert to the perennial classic—“it’s a ponzi!”

Anyways, chances are you didn’t click on this letter to read about Ethereum becoming a green blockchain—you’re here because of the midly clickbaity jab I took at traditional artists.

So let’s turn our attention to the meat and potatoes of this letter: the damage caused to the environment by traditional art.

For sake of clarity from hereon out, when I use the term “traditional art” I mean art that is neither digital nor on the blockchain. And while there’s a number of artists we could put a spotlight on, today I’d like to talk about just four: writers, painters, photographers, and sculptors.

The Ecological Damage of Traditional Art

Part I: Writers

Let’s start with the obvious: the publishing industry is responsible for the death of a staggering amount of trees. You were probably already aware of this on some level, given our complete reliance on paper, cardboard, newspapers, magazines, textbooks, and more, but the extent to which the publishing industry adds up may come as a shock.

There were more than 825 million books printed in the US alone in 2021; the US also consumes 32 million trees per year just for books. Unfortunately this is also exacerbated by the fact that The National Wildlife Federation estimated that 640,000 tons of books are annually sent to landfills in the US without being recycled).

According to the journal Nature, it is said that the number of trees worldwide sits around 3 trillion—while a staggering amount, that apparently accounts for a 46% decline since the beginning of human agriculture 12,000 years ago, a number which is not nearly being replenished at the same rate.

Worldwide, an estimated 15 billion trees are felled every year. And while deforestation for the purpose of creating farmland or crops by far dwarfs the environmental impact of the publishing industry, it is hardly negligible or worth scoffing at.

As a writer, there’s no feeling like seeing your work on the printed page. But something every writer needs to reconcile with is the fact that unless their work is digital only, or published with 100% recycled paper, they are contributing to deforestation and landfills being filled: it’s a dirty but known secret in publishing that unsold books which could not be liquidated are turned into pulp or sent off to landfills.

It also turns out that the paper industry is heavily reliant upon copious amounts of water. The standard for the manufacture of paper and pulp requires roughly 17,000 gallons of water per ton of paper in the US; some of the most efficient (but admittedly few) facilities can reduce this number to around 4,500 gallons per ton by recycling paper and other measures which improves the efficiency of their production, and cuts down on water costs. But they are not the norm.

However, even with top-tier technology, the best case scenario is still not renewable: recycled paper deteriorates over time as the paper fiber tensile strength gradually wears down with repeated recyclings. According to the Paper Federation of Great Britain, paper is more or less spent after 5 or 6 times being recycled (and is frequently recycled less than that). What this means is that there will always be a substantial need for the harvesting of trees to keep up with paper demands. Furthermore, some books (like hardbacks) require a higher quality paper which makes them less green and more difficult to recycle.

Writing: the NFT & Web3 Advantage

Writing is an industry that has become progressively more digital even before the blockchain, as people increasingly turned to online sources for their news, and e-readers for their favorite books.

Reading on a Kindle fells no trees and can hold thousands of books on one device, eliminating the need to manufacture, distribute, transport, return, or dispose of books. Additionally, digital works do not require managed forests, tens of thousands of liters of water, or the CO2 emissions of factories and transport. Even if your e-reader one day ends up in a landfill, it is still objectively better than the equivalent ecological cost of the books you would have read.

One caveat however: this is admittedly a field where NFTs have yet to prove themselves: writing as a whole has yet to take off on the blockchain. But while the distribution of books as NFTs has not caught on as of yet, it almost certainly will in the future.

With the possibility for royalties to go straight to the author and bypass agents, publishers, and online publishing platforms, authors could save upwards of 15-30% by selling directly over the blockchain via NFTs, cutting out the middle man, and doing the environment a favor all at once.

It’s also possible that traditional publishers could transition to web3 and use NFTs to save on costs for distribution, regulate royalty management, and set customized lending standards.

The Ecological Damage of Traditional Art

Part II: Painters

It is rather difficult to paint in an environmentally friendly way. Quite simply, the materials most painters own and use on a regular basis are overwhelming hazardous to the environment. Paints in general pose a risk to air quality, and come with numerous dangers in every stage of their journey from manufacture to transport, to use, to disposal.

When we talk about paint and air quality what we’re really referring to are VOCs, or Volatile Organic Compounds. I will not fear monger you—many VOCs are benign, and play a part in everything from giving odor to a particular scent, and can be found in the natural world in the interaction between plants and animals, aiding pollination, and allowing some creatures to avoid predation. That is not what I’m talking about.

As far as painting goes, many VOCs are damaging to the environment and human health. While many VOCs in paint are not acutely toxic, they can pose long term, detrimental, and ongoing effects to one’s health, especially during the drying and curing process. This is especially true in the case of painting indoors, with the Environmental Protection Agency claiming that the concentration of many VOCs may be upwards of ten times as high indoors as outdoors. And, were someone to make the mistake of applying an exterior paint to an interior surface, that danger can persist significantly longer.

VOCs in paint contribute to the creation of ozone and smog, particularly in urban areas. This affects breathing capability and can target the ears, eyes, nose, throat, and lungs in a number of detrimental ways—and that’s just in healthy individuals; VOCs are especially damaging to those with weakened immune systems, respiratory illnesses, and other conditions which make them otherwise more sensitive than the general population.

Pigments, the lovely ingredients which give color to paint, is another can of worms. Several are notoriously toxic, including things like mercury chromate, chromium oxide, cadmium sulfide, and cobalt chloride. Pigments can also synthetically be manufactured, but again, at a cost: synthetic pigments are largely derived from petrochemicals and/or coal tars.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, pigments are held in place with emulsions of acrylic polymers and plasticizers to help the pigment bind and dry in place. Additionally, solvents in paint (which are usually oil-based, with the exception of alcohol) are often made with toxic organic chemicals as well.

Indeed, there are environmental risks at every stage, from the gathering and extraction of certain pigments, to the grinding and milling process, to the eventual production of paints in factories including all of the chemical binders and plasticizers that entails, to the transport of the paint to the store you purchase them from, to the actual chemicals shed as VOCs during painting, the inherent contamination risk of spills, to the difficulty of their proper disposal—you can see how many ways this may not be optimal for the environment.

As I just mentioned, paints and solvents can be especially damaging when it comes to improper disposal. If an artist tosses the wrong material away in the garbage willy-nilly, it can wreak havoc on the landfills where they eventually end up. These paints and solvents then work their way into the soil and run off into lakes, rivers, and other bodies of water, poisoning the ecosystem, threatening aquatic life, and sometimes even damaging the water supply. Oil based paints are especially at risk of being a source of contamination if improperly disposed, posing a problem both for people and the environment.

I don’t want to suggest that it’s only ignorance or laziness that gets painters into this mess, however: sometimes it’s merely an accident. But accident or not, without the knowledge and proper means of cleaning up, the environmental impact can be severe, especially when certain toxic materials are washed down drains, into sewers, or find their way into any other water drainage system.

One especially unpleasant group of chemicals found in many spray paints, paint thinners, and some acrylic and oil paints (especially the cheaper varieties) is benzene or benzene derivatives, which are known carcinogens. The CDC notes that it is especially harmful with prolonged exposure. Commercial painters are at even greater risk, but we’ll just stick with traditional artists today.

A growing number of paints today advertise that they contain no VOCs, but that is not to say that they are “safe”: many VOC-free paints still give off hazardous vapours in the form of ammonia, hydrocarbons, xylene, and gycols, among others. And even in the VOC-free paints that are safe to humans, they may not be quite as forgiving on the environment itself.

Painters may also pose a threat to their own health, as many chemicals that are found in cigarettes can also be found in some paints: chromium and cadmium, among others, can be found along with various solvents, styrene, and toulene.

Another factor for painters to consider are the environmental costs their hobby or profession entails: framing, exhibitions, and the transportation of supplies and materials all come at a cost. Any artist who is in demand to display their work in various cities or countries will quickly accrue an abundance of greenhouse gas emissions from travel and transport.

Acrylic Paints

Acrylic Paints contain varying levels of toxicity, and are plastic in the sense that their pigments are held in place with acrylic polymer emulsions, oils, stabilizers, and plasticizers which are used to hold the material in place and stick to substances as it dries. They may include or produce chemicals such as formaldehyde, ammonia, acetal, ethylene oxide, manganese, and more.

Acrylic polymer emulsions are frequently the binder for acrylic paints. Methyl methacrylate is one such example, which is reportedly toxic to aquatic life, and can react with other substances in the air to form photochemical smog.

Many of the pollutants found in acrylic paints are carcinogenic, including: styrene, xylene, benzene, and butadiene. These have been linked to kidney damage, brain damage, leukemia, lymphoma, and various blood disorders.

Acrylic paint may also include a number of biocides. Biocides are used in paint as a means of preservation, preventing mold and bacteria growth. Unfortunately, biocides can include toxic chemicals like benzisothiazolinone, methylisothiazolinone, and Chloromethylisothiazolinone.

Thankfully, there are some responsible companies which produce biodegradeable acrylic paints which substitute many of the more harmful materials with less dangerous ingredients that are capable of breaking down safely and reducing its environmental impact. Taken a step further, some artists make their own acrylic paints, even going so far as to grind their own pigments from local flora or organic matter like mushrooms.

Oil Paints

While oil-based paints have the benefit of avoiding plastics in its binders unlike acrylic paints, they are still far from safe: toxic heavy metals can be found in several oil-based paints, particularly in many white, blue, red, and yellow varieties. Though this is unlikely to present any immediate threat in small enough quantities, the accumulation of these heavy metals may pose a problem to the environment. Furthermore, oil paints tend to linger, take longer to dry, and shed more volatile organic compounds into the air.

Ironically however, the environmental danger of oil bail paints is perhaps most present in what it takes to clean them up. Oil based paints require special handling and proper disposal. Paint thinners (used not only to thin the paint, but also for cleaning purposes) often contain highly toxic substances, which if not properly disposed of, can seap into the soil, pollute groundwater, and make its way to sewage systems or large bodies of water. Although local laws generally regulate the disposal of toxic waste such as this, not everyone is especially careful or as cautious as perhaps they should be.

Painting: the NFT & Web3 Advantage

The painting above clearly demonstrates that digital artists are a force to be reckoned with—Gary’s work was painted entirely by hand with a mouse, nine years before digital artists even had the convenience of an iPad to draw with!

Given the capabilities of digital painting, and the numerous ecological concerns of traditional painting, is it any surprise that I suggest that more artists should consider making the digital switch?

Apart from the admittedly poor conditions that go into the initial manufacture of most tablets or electronics, digital artists have few recurring environmental concerns beyond the electricity required to run their device.

Traditional artists who make the switch to digital (including NFTs) can avoid transport costs, distribution costs, and cluttering up the planet with more stuff, all the while saving a ton of money on materials and supplies, and drastically reducing their carbon footprint.

Furthermore, at least to my knowledge, nobody has gotten rapid or irregular heartbeats, leukemia, cancer, respiratory illnesses, or polluted their local water supply from drawing on their iPad.

Taken a step further, digital artists who sell their work as NFTs can interact with their audience in more personal and custom-tailored ways: this includes token-gating for more intimate or selective communities, rewarding loyal members with special drops or promotions, and building a more personal and direct line of communication between the artist and the audience.

Perhaps greatest of all, painters who embrace NFTs may set their own royalty rates on certain marketplaces (if you can’t, it’s not a marketplace worth using and should be confined to the trash heap of bad web3 ideas). Having spoken with dozens of NFT artists, this is what they all tell me was the initial appeal for making the switch to NFTs.

Better for the environment; better for the artist; better for the wallet.

The Ecological Damage of Traditional Art

Part III: Photographers

Let’s open with a Grand Canyon sized caveat here—photography today is undoubtedly more environmentally friendly than the industries built around writing or painting. By a long shot. Most professional photographers today have transitioned to DSLRs (digital single-lens reflex cameras) and moved away from the old ways.

Back then, the traditional method of finishing film relied upon an abundance of toxic chemicals for its processing and development. In darkrooms—named for the location in which a photographer could develop away from light and prevent highly sensitive films from overexposure—they sat among a number of chemicals which may have included: hydroquinone, ammonium thiosulfate, sodium carbonate, para-phenylene diamine, sodium sulfite, acetic acid, boric acid, phenidone, and various dimethyl or diethyl derivatives, among others.

But as already mentioned, photographers these days are generally quite content to use their DSLR (or let’s face it, even their phone) to take photos.

This has already been a welcome benefit to the planet as less print rejects are created and destroyed (good, as photographs burned emit some rather nasty chemicals), or otherwise trashed: recycling with traditional photography isn’t really a thing, as the silver halide crystals held in place between the gelatin layer on paper is not biodegradable and thus cannot be recycled.

Most hobbyists today are also content to stick to digital means, leading to a massive reduction in wasted film, spent chemicals, or disposable or polaroid cameras (outside of a minority of people who enjoy staying in that lane).

It is worth noting that nothing, even digital photography, comes without a cost. The production of DSLR’s sensors, as well as much of the computer equipment used to edit photos requires rare earth elements that are difficult to acquire, especially in an environmentally safe manner. To a lesser extent, batteries, memory cards, and various photo accessories can add up to the waste as well. This is not a knock against photography specifically (after all, all NFTs and blockchain development occurs on computers which face a similar problem) but merely an observation that digital photography is significantly less damaging to the environment than the alternative.

There is one environmental edge concern in animal photography specifically worth mentioning, however. This particular issue isn’t a risk to the water, air, or land, but rather, to the actual animals of the planet themselves.

I’m talking about camera traps.

Camera traps are speciality equipment used to take photographs when triggered by an animal setting off a motion sensor. They have been used for decades in conservation by scientists and researchers and are generally pretty safe when used properly. But like everything, there are risks.

The issue is that some photographers try to game the system in their favor and increase the probability of their subject showing up by baiting their camera traps with food. Now ideally this wouldn’t ever be done, but admittedly there are minimal risks if the animal is fed one time only, or very irregularly. The problem is that anything more than irregular feedings have been known to cause animals to become accustomed to the tasty handouts and change their patterns. Even more concerning, it increases the probability of run-ins with humans, which puts them at risk. Especially in more remote locations, if the animal is wild or seen as a dangerous threat, they may end up shot on sight, purely for wandering where they shouldn’t have and guilty of only looking for more food. I’ll grant you that this is probably the smallest, most edge case in this letter, but it remains an ecological concern worth mentioning, given that it can lead to the loss of animal life.

Exhibitions are a more common source of waste for photographers who are still displaying their works in physical environments. Getting one’s work printed, framed, shipped, displayed, (and if the artist is lucky) sold and shipped, expends a lot of material and environmental costs.

In all likelihood, one of the greatest ecological concerns for photographers unfortunately affects both the traditional and digital variety—transportation. As many photographers seek out rather specific flora, fauna, landscapes, or people, this is an art form which requires more travel than most, especially internationally. This is a problem, as air travel in particular contributes heavily at 4% of all human-induced global warming—a higher output than most countries! As there are often not many ways around air travel, it’s essential that photographers look for other means of implementing greener practices in their line of work.

Photography: the NFT & Web3 Advantage

Even in a field that has already made great strides and technological innovation, the move towards digital photography NFTs is poised to help photographers remain ecologically conscious as well as extend their reach to their audience.

Nearly any way you cut it, NFTs are less wasteful and more environmentally friendly than any traditional photographic practices past or present, for many of the same reasons already given for writers and painters.

Of special interest to photographers should be the growing trend of digital exhibitions on the blockchain: indeed, entire exhibitions can be hosted for cheap, or even free, with the artist’s work proudly displayed. Guests who attend the event and admire a certain piece can purchase it on the spot with a simple click or two, all done without anyone needing to leave the comfort of their home. The transportation costs to host an exhibition in web3? $0. The material cost to host an exhibition in web3? Also $0. No printing, framing, transport, or shipping required.

Photographers who embrace NFTs can also benefit from the same boon every artist on the blockchain has—the ability to cut out agents, remove middlemen, and set royalty rates in perpetuity (I will continue repeating this fact until this is common knowledge to everyone).

The Ecological Damage of Traditional Art

Part IV: Pottery & Sculptures

Sculpting often gets overshadowed and overlooked, especially in comparison to the other art forms we’ve already discussed. It is a technically challenging 3D art form that can be made from a great deal of potential materials, some of which are more or less neutral in their environmental impact, while others are a cause for concern.

In mold making for instance, Methyl ethyl ketone peroxide (MEK-P) is sometimes used in combination with polyester resins as a hardener or curing agent in plastics. It is highly damaging to the environment if handled or disposed of improperly, being acutely toxic to aquatic life and even having slight long term effects as well.

One material extracted from the earth and used in a lot of sculptures—clay—has a long and storied history, with its most common association being in the production of ceramics (it’s worth mentioning that not all ceramics are sculptures). While clay seems relatively harmless at first, the extraction of clay has been tied to a number of ecological issues such as deforestation, erosion, and the silting of bodies of water. In addition, the mining activities surrounding clay extraction can modify stream morphology by distorting the channels or diverting stream flows.

The process of pulling a single substance like clay from the earth isn’t as straightforward as it might seem. Nature doesn’t keep things in isolation, and when extracting clay other substances are frequently kicked into the atmosphere as well: various mineral dusts, iron, and whatever else was trapped in the immediate area surrounding the clay.

And while pottery is more reusable than many materials (a definitely plus in the eco-friendly category), the high fuel use required for the firing of clay pottery (which is generally done twice) can be costly in terms of energy regardless of whether it’s using gas, electricity or other methods—although fossil fuels are most common. Carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and black carbon are just a few of the chemicals which are released in the firing process.

One of many studies on the effects of clay harvesting took place in Abonko, Ghana, where the local population is heavily reliant upon clay harvesting and crafting for work. It paints a less than glowing portrait:

The environmental consequences far outweigh the economical benefits of clay harvesting at Abonko. Ninety-five percent (95.0%) of the respondents harvest clay near residential areas and on farmlands which as a result made food foodstuffs very expensive in the locality. Because clay mining has not been properly regulated by mandatory agencies like Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), most water bodies in the community have been polluted as a result of clay harvesting. Huge agricultural farmlands have been destroyed and because there is no training and supervision of their work by EPA, there has not been land reclamation after clay harvesting. Most of the respondents have low educational background and therefore have little knowledge about environmental degradation.

- To read the full study, you can click here.

You can find similar studies from regions all over the world coming to more or less the same conclusions. Granted, these communities would be better off if they were following EPA regulations as stated in the study, but that’s exactly my point: there’s often a chasm between what should be done, vs the reality of what is done. The planet doesn’t care about our intentions; it cares about what is actually put into practice.

Like a lot of mining and resource extractions, there are ways to do so that is more thoughtful and conscious of its environmental impact, but as these methods are often more expensive, slower, and require people with higher levels of education or training, it’s often not the case.

Another substance which sees a lot of use in sculptures is fiberglass due to it being a cheap, light, and durable material. But its greatest asset is also its biggest ecological concern: it stubbornly won’t break down.

Fiberglass will not decompose and, with the proper treatment, is seemingly unaffected by the weather of all four seasons. It is also highly resistant in general, shrugging off a lot of acids, salts, or gases. So while it may not leak into the ocean or poison drinking water, it will likely end up in a landfill at some point.

Fiberglass is not recyclable.

As a final aside, while the substance itself may be harmless enough to the touch, the manufacture of fiberglass creates styrene and other pollutants, which as we already established, affects the air quality.

Perhaps the most classic and famous sculpture material of all is marble. While exquisite and beautiful marble is—you guessed it—also problematic, being an unsustainable, non-renewable material, the extraction of which is expensive, energy intensive, and often dangerous.

Marble extraction often requires the use of small explosives, drilling, and vertical cuts to free it from the rocks around it. This process kicks up marble dust, which affects the quality of the air, contaminates water sources, and wrecks soil quality earmarked for agriculture; it may also disrupt the respiratory track of artists who inhale too much of it.

Sculptures: the NFT & Web3 Advantage

The benefits of forgoing traditional sculptures in favor of digital models as NFTs on the blockchain should be familiar by now (I realize I’m beginning to sound like a broken record): it requires less energy to produce, does not exhaust any materials (renewable or non-renewable), can be transported from gallery to gallery at the click of a button, saves the artist a lot of money in materials, allows the artist to set royalty rates in perpetuity, will not contribute to any landfills, greenhouse gases, or affect soil quality, etc, etc. For artists concerned about taking what is effectively a 3D art and rendering it on a screen, there are solutions for that as well: plenty of software today enables artists the ability to work with 3D modeling and sculpting. There are even VR solutions as well.

As NFTs in online web3 museums, guests can visit from all over the world, and examine the sculptor’s work in three dimensions, just as if they were in person. The effect can even be further amplified with the use of a VR headset.

A Greener Technology for a Greener Future

It’s official: the talking points lobbed at NFT artists and collectors are no longer defensible or accurate. Ethereum is a green blockchain, consuming drastically less energy per year than the video games or Netflix people consume.

Not only is Ethereum green, but the vast majority of NFT blockchain alternatives are Proof of Stake as well: Solana, Cardano, Flow, Tezos—they’re all green.

I challenge naysayers to demonstrate how acrylic or oil painting with all of its questionable, toxic materials is somehow safer for the environment than an iPad with Procreate making NFTs on a Proof of Stake blockchain. Show me how the publishing industry and its water wasting, deforesting, landfill filling system is better for the planet than a digital marketplace full of unburnable texts that can store a library on a single device. Let me know how clay, marble, and fiberglass statues are a more responsible ecological decision than designing their equivalent digitally.

Photographers…well, honestly, you’re the only group who came out considerably better in my research than I initially expected! I think you’re headed in the right direction, perhaps because you were already early adopters of this digital transformation—maybe just try to keep air travel to the essential and consider holding more of your exhibitions in web3 rather than the real world.

For the record, I am not pushing for a future of only digital artwork NFTs. Art exists in countless forms and mediums, and I believe that it enriches our lives in different ways: there’s likely room for everything and everyone, within reason and in moderation. But I also think that it’s important to consider as artists how our actions affect the world around us. I’ll also go on record to say that everyone’s situation is different, and what is feasible for one creative individual or family may not be for another.

Nonetheless, if your goal is to be a sustainable artist doing as little harm to the planet as possible, it’s extremely difficult to argue that anything other than digital art and NFTs on a Proof of Stake blockchain is the answer.

I understood the hesitancy of artists in embracing the blockchain when Ethereum was an inefficient Proof of Work system; I shared many of the same concerns. But those days are over, and you no longer need to dip your toe in the pool—you can jump in with a clear conscience.

Technology innovates.

With those innovations comes improvements in efficiency, power, and energy use. The fact that blockchains have only existed since 2009, Ethereum came out in 2015, and we’re somehow already better for the environment than all four of the art forms I wrote about today is quite impressive, especially when you realize that they had centuries to millennia to innovate.

That is just one of many reasons why I work in web3 and am passionate about all of the innovation coming out of the space.

The onus lies on all of us to step up and make our art in more ecologically conscious and responsible ways. But let us not lose sight of our true target. At the end of the day we need to acknowledge that no matter the personal changes we make on an individual level, no meaningful environmental change can come without our industries being held to account.

Art waste, as lamentable as it is, is just a drop in the bucket. Never forget that industry and fossil fuel combustion accounts for 78% of all greenhouse gas emissions. After that, “agriculture, deforestation, and other land-use changes” are the largest culprits.

There’s no better way to sum everything up and bring this letter to a close than by sharing the legendarily astute cartoon (now meme) by writer and New Yorker cartoonist, Tom Toro.

Thank you all for reading. I promise the next piece won’t be so heavy.

Written by: Brad Jaeger

Director of Content @ Curious Addys (say hi on Twitter!)